Shifting Gears Part II: International Human Rights Violations

In preparation for the campaign launch of “Shifting Gears Part II: Human Rights in the EV Value Chain,” Investor Advocates for Social Justice (IASJ) is releasing an educational blog series to highlight salient human rights risks implicated in the electric vehicle (EV) transition. Read the first installment here.

Although the EV transition has been viewed as an important component of combatting the climate crisis, the EV supply chain currently presents a host of significant environmental and human rights concerns. Central to this is the heavy reliance on minerals, with the average EV requiring six times the mineral inputs of a conventional internal combustion engine (ICE) car. The International Energy Agency (IEA) has identified eight important transition minerals for EVs and EV batteries: lithium, nickel, cobalt, graphite, manganese, copper, aluminum (which comes from bauxite), and rare earth elements (REEs). Many of these minerals are extracted from countries with poor human rights records, high levels of corruption and inequality, armed conflict, and political instability. In this second blog installment, IASJ will present a deep dive into the key human rights risks associated with mining and processing these 8 minerals.

Associated human rights violations are related to four broad categories: 1) indigenous and land rights, 2) environmental and health rights, 3) rights implicated in conflict-affected and high-risk areas, and 4) labor rights.

Human Rights by Focus Mineral

1) Indigenous and Land Rights

Due to its land-intensive nature, mining often interferes with indigenous peoples and local communities’ rights.* A recent study showed that more than half of mining projects worldwide are located on or near indigenous lands. Mining projects may force people from their land, prevent access to clean water, and can expose communities to harassment and violence by mine or government security. These impacts are disparately felt by women, who are often barred from consultation and land negotiations. For Indigenous Peoples, mining projects frequently violate the right to free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC). This is the right to give or withhold consent on projects that affect their communities and lands without coercion, intimidation, or manipulation. Although many mining companies make commitments to respect Indigenous rights, their operations continue to violate FPIC.

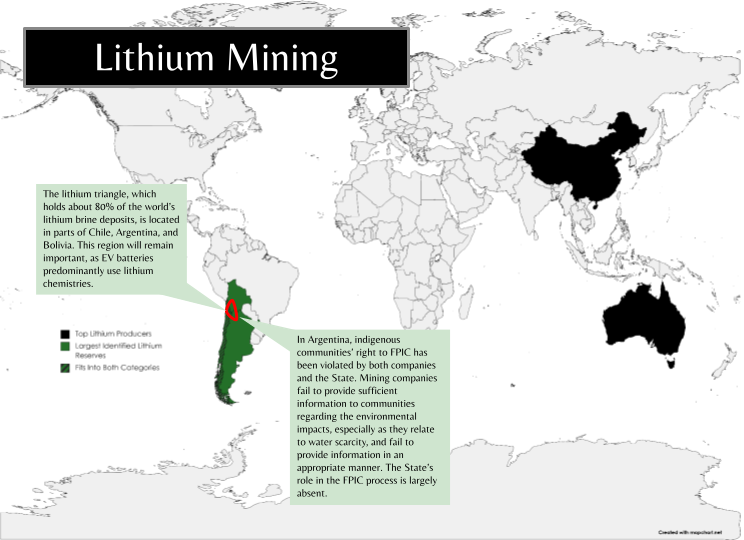

This has been the case in the lithium triangle, a region in Argentina, Bolivia, and Chile that holds about 80% of the world’s lithium brine reserves. Lithium mining is water-intensive and is concentrated in one of the world’s most arid regions.

Indigenous communities in the lithium triangle face adverse threats to agricultural activities and grazing for livestock. An investigation in Argentina’s Jujuy province found that mining companies violated FPIC of Huancar and Pastos Chicos Indigenous communities. Specifically, the companies withheld information about environmental impacts.

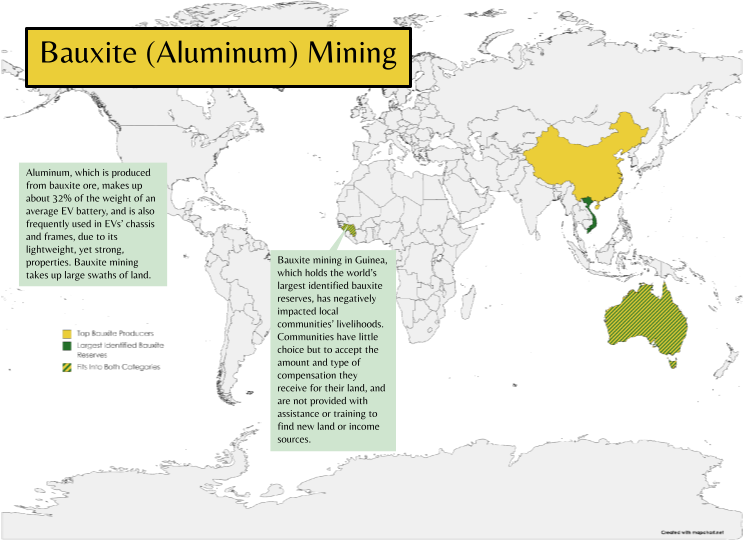

Similar concerns are present in aluminum, which makes up about 32% of the weight of an average EV battery. Aluminum, which is extracted via bauxite mining, involves surface level or “strip” mining. This takes up large swaths of land, often affecting ecological systems on which local communities depend for their livelihoods. In Guinea, the third largest producer of bauxite, Human Rights Watch documented mining companies circumventing customary land rights of local communities, which has led to forcible eviction and arbitrary interference with their land rights. Furthermore, communities have little say in the amount and type of compensation they receive, which usually does not provide for assistance or training to find new land or income sources.

Other emerging concerns include forcible eviction of families in the DRC to make way for copper and cobalt mines.

2) Environmental and Health Rights

Mining leaves a lasting mark on the land and peoples in the regions in which it takes place. Moreover, chemicals used in mining frequently pollute the air, land, and water systems of neighboring communities.

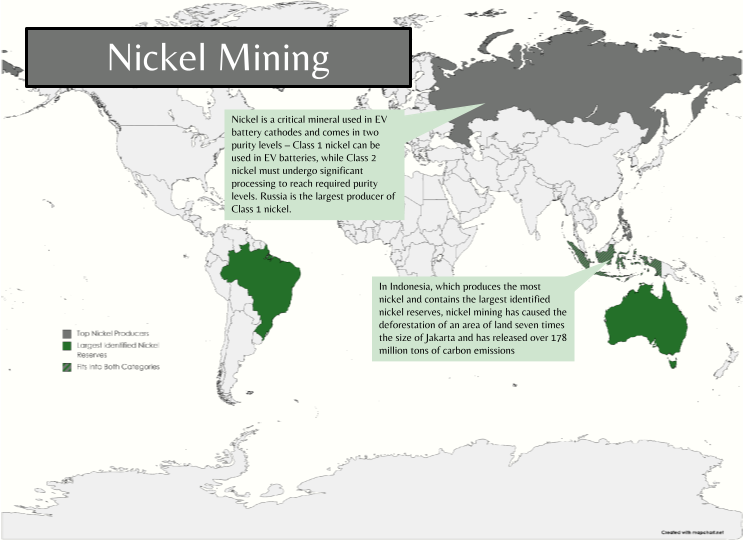

For example, Indonesia is the world’s leading producer of nickel, and the industry is rife with environmental and social impacts. In the Indonesian provinces of Central Sulawesi and Southeast Sulawesi, nickel mining has resulted in the deforestation of over 500,000 hectares of land and has released over 178 million tons of carbon emissions.

Coal-powered processing plants to refine nickel in Indonesia release sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, and coal ash, increasing respiratory infections and other health issues. In addition, waste from nickel mining often pollutes water sources and disrupts local fishing industries.

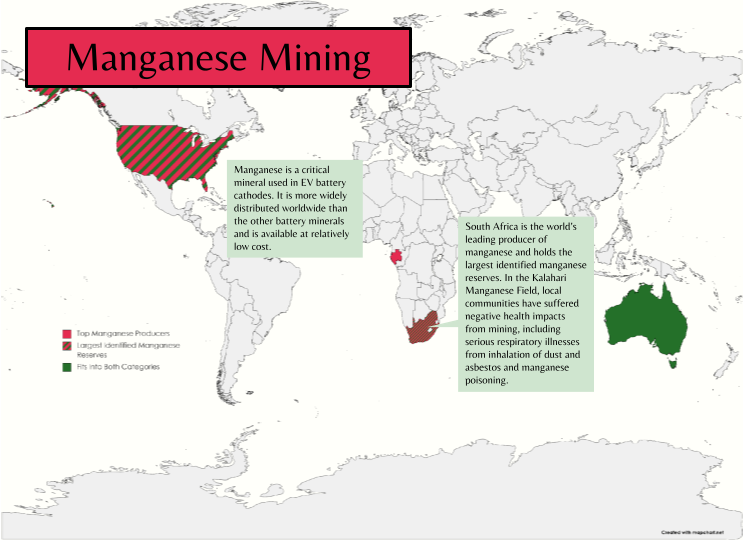

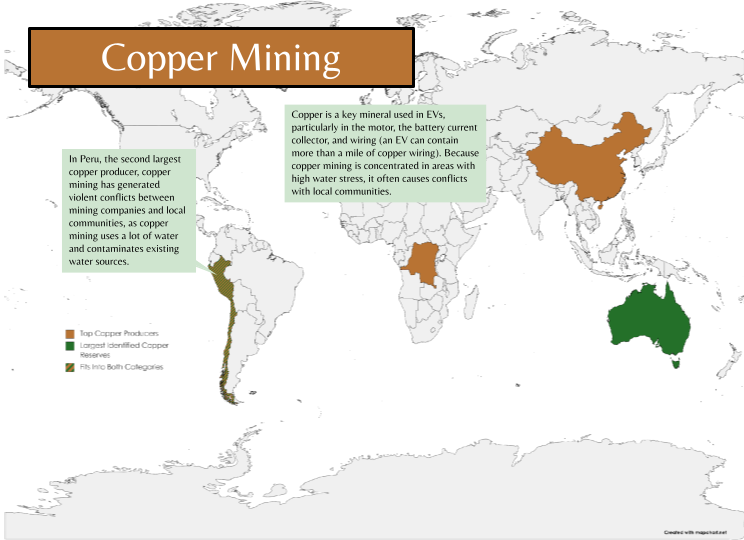

Manganese, another EV battery transition mineral, is principally mined in South Africa. In the Kalahari Manganese Field, manganese mining has been connected to serious health impacts from water pollution, dust inhalation, and manganese poisoning. Other minerals like copper are frequently mined in places of high water stress. In Peru, the world’s second largest copper producer, 20 community members were allegedly evicted and illegally detained by a copper mine’s security workers. Communities opposed plans to expand the mining project, which would result in increased water demand and higher levels of water contamination in the region.

3) Rights Implicated in Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas

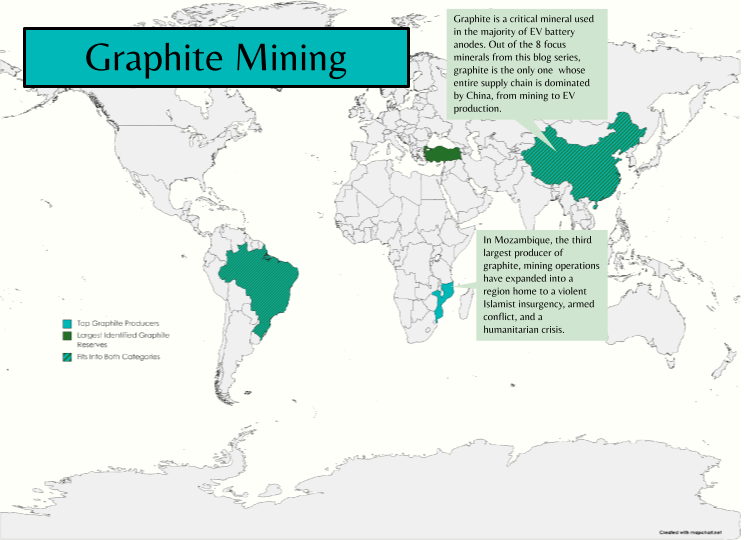

According to the OECD, conflict-affected and high-risk areas (CAHRA) “are identified by the presence of armed conflict, widespread violence or other risks of harm to people.” Sourcing minerals from CAHRA may exacerbate conflict and violate human rights. Graphite is currently the most common mineral used in EV battery anodes and is found in large quantities in Mozambique. An armed conflict is currently waging between the Mozambican government and the Al-Shabab group, which is affiliated with ISIS. The conflict region is also home to one of the world’s largest graphite mines. For locals of the war-torn and poverty-stricken region, the mine, which has displaced some people and has not provided any sustainable economic benefit to them, may become an inflection point in the insurgency. Graphite mining in Cabo Delgado “bears risks of exacerbating root causes of local conflicts” and “undermining an energy transition that is just, fair and prioritises the creation of long-term benefits for affected local communities.” Recently, Tesla reached a deal with the mining company in charge of the graphite mine, in which the mining company will supply Mozambican graphite.

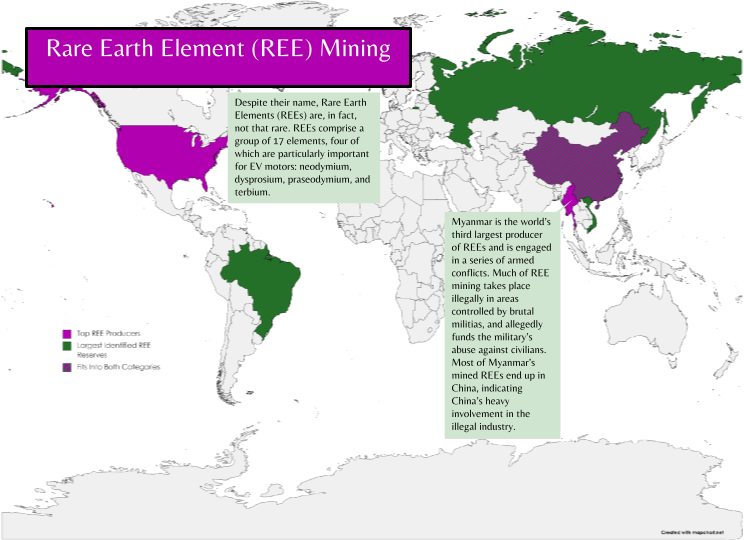

Myanmar, the third largest producer of REEs, is engaged in a series of armed conflicts with non-state armed groups. The Kachin Special region, which provides the world’s largest supply of REEs, is run by militias affiliated with Myanmar’s brutal military regime. Illegal mining has been reported in this area and reports indicate China is heavily involved. A recent Global Witness report stated there was “a high risk that revenues from rare earth mining are being used to fund the military’s abuses against civilians, which have intensified since its February 2021 coup.” In addition to the myriad of negative health and environmental impacts related to mining for REEs in Myanmar, local residents frequently receive threats of violence from the militia if they ask for an end to the expansion of mining on their ancestral lands.

4) Labor Rights

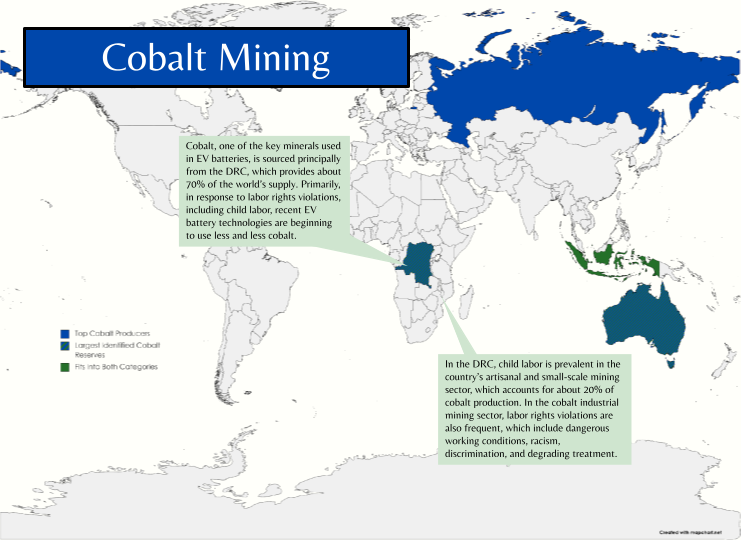

One of the most prominent labor abuses in the EV supply chain is connected to child labor in cobalt mining in the DRC. A seminal Amnesty International report detailed the atrocious working conditions of children mining for cobalt, with risks of cave-ins and lack of protective equipment, physical and sexual abuse, and low wages. Most recently, the U.S. Department of Labor’s annual Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor report emphasized the continued prevalence of child labor in cobalt mining, estimating between 5,000 and 35,000 child miners in the country’s artisanal and small-scale mining sector.

In addition to child labor, other rights abuses have been documented in the cobalt industrial mining sector. A recent report details dangerous working conditions, inadequate access to healthcare, limited or non-existent freedom of association opportunities, low wages, and racism, discrimination, and degrading treatment. According to the report, “the heart of the problem is the subcontracting model used by the multinational companies to hire their workforce,” a model that “erodes workers’ rights and provides cheap labour.”

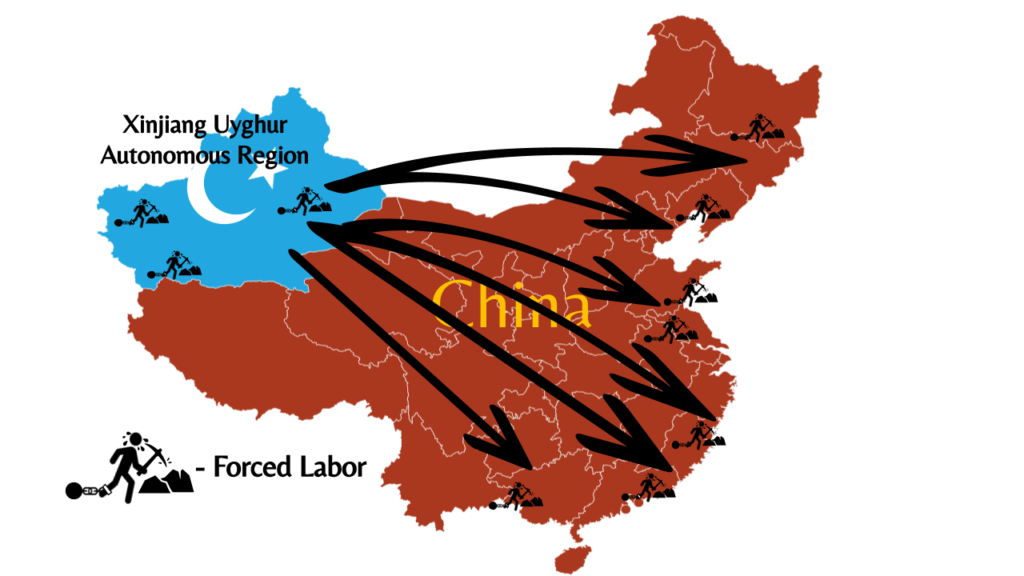

In China, despite the country’s repeated denial of forced labor in the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR), home to a significant number of Uyghur and other predominantly Muslim ethnic minority groups, the UN Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights recently released a report detailing the numerous human rights violations committed against these minority populations, including forced labor, both within the XUAR and across China. Most recently, a report determined that “parts manufacturing, materials processing, and mineral mining associated with the automotive industry is substantially tainted with forced labor.” According to the report, practically every major automakers’ supply chains – including Tesla, GM, Ford, MBW, and Volkswagen – is connected to force labor in the XUAR.

Conclusion

A just and sustainable future can only be secured through a just and sustainable transition. An EV transition that violates human rights and harms the environment would be just repeating the sins of the fossil fuel industry. As shown in this blog, the 8 key EV transition minerals each carry with them a host of documented human rights risks. Due to the complexity of EV supply chains, automakers have largely ignored their human rights responsibilities, and the poor and marginalized often suffer as a result.

Truly sustainable solutions respect human rights at every step of the process: from sustainable sourcing practices, to respecting labor rights in EV manufacturing. The next blog in this series will focus domestically on the EV transition’s human rights impacts in the United States.

* Indigenous rights and land rights are included here for the sake of ease in groupings. However, this in no way implies indigenous peoples’ rights are the same as local communities’ rights. See First Peoples Worldwide’s statement.