Shifting Gears Part II: Human Rights in the EV Value Chain

The Salar de Atacama in Chile is the world’s largest and highest-grade commercial lithium brine deposit.

Investor Advocates for Social Justice (IASJ) is using our voice as faith-based and responsible investors to engage with portfolio companies in the automotive sector. Building upon our 2020 capstone report, Shifting Gears: Accelerating Human Rights in the Auto Sector, IASJ is launching a new phase of our campaign to address human rights in the electric vehicle (EV) transition. In anticipation of Shifting Gears Part II: Human Rights in the EV Value Chain, IASJ is releasing an educational blog series to highlight some of the most salient human rights risks implicated in the EV transition. In this first installment, IASJ provides an overview of the EV supply chain, trends in technology, and key human rights considerations for the automotive sector.

Fueled by the climate crisis, and the resulting goal to reach zero net emissions by 2050, the production and use of electric vehicles has made significant headway, especially during the last decade. Promising a sustainable form of transportation, EV sales made up almost ten percent of global car sales in 2021, with 6.6 million EVs sold. Although in 2021, more than half of global EV sales occurred in China, there is significant momentum globally for increased EV use, as regions and countries, as well as automakers, have committed to increasing EV production. The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates an average of 200 million EV sales by the year 2030.

The EV transition has been touted as a crucial component for combatting the climate crisis, but as it stands, the EV supply chain currently presents significant environmental and human rights concerns. For example, EV components, such as minerals and metals that compose the EV battery, are often sourced and processed in countries engaged in conflict or with poor human rights records. Additional concerns regarding the reuse and recycling of EV batteries persist as the world transitions to large-scale production and use of EVs.

The fundamental difference between an internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicle and an EV is the EV’s complete reliance on electricity as its power source. Key to this green technology is the EV battery, which accounts for about 40% of an EV’s total value. Typically, EV battery packs are made up of thousands of individual battery cells, which contain four main components: anode, cathode, separator, and electrolyte.

While battery technologies for use in EVs are ever evolving, lithium-ion (li-ion) batteries are currently the most popular type of battery due to their small size, light weight, and high energy storage capacity. Li-ion batteries typically contain a variety of minerals in their cathode (e.g. lithium, nickel, cobalt, manganese) and graphite in their anode. The electrolyte solution is a liquid consisting of lithium salt, organic solvent and additives, and the separator is typically made of synthetic resin, such as polyethylene and polypropylene. The remaining battery parts contain mostly aluminum, copper, steel, coolants, and other electronic parts. According to the IEA, the three most important minerals for li-ion batteries are lithium, cobalt, and nickel, with graphite and manganese close behind.

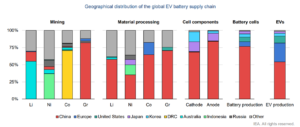

The EV battery supply chain can be broken down into six stages: mining, raw material processing, cell component production, battery cell/pack production, EV production, and recycling/reuse. Mining of transition minerals lithium, nickel, and cobalt takes place across the globe. The largest producers of lithium are Australia and Chile; the largest producers of nickel are Russia, Canada, and Australia; and the largest producer of cobalt is the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), with over 70% of the global cobalt production. However, from the raw material processing stage to the EV manufacturing stage, China is the dominant player at all stages (see graph below). Additionally, around half of the global capacity for battery recycling is concentrated in China.

Given the global reach of EV battery supply chains and their complexity, human rights violations, including environmental-focused impacts, are prevalent throughout the supply chain. Because EV batteries require key minerals that are often mined from countries with weak regulations, poor records of human rights violations, and/or the presence of conflict-affected and high-risk areas – the mining stage is particularly rife with human rights violations. Far from being exhaustive, this section will present a few of the most severe and prevalent human rights violations, which include:

Child labor has been linked to cobalt mining in the DRC, where more than 70% of global supply comes from. In these mines, children have been documented working in dangerous conditions, with risks of cave-ins and lack of protective equipment, and face physical and sexual abuse, as well as earn very low wages. In China, recent reporting from the UN OHCHR alleges that labor abuses committed against the Uyghur population is not limited to the Xinjiang region, but also extend throughout China, as surplus labor and labor transfer schemes forcibly ship members of this population to other regions to work. Because the majority of the raw material processing and EV battery production take place in China, forced labor is potentially part of the EV supply chain. In other parts of the world, labor rights abuses, including unsafe working conditions and unfair compensation, have been documented extensively in the mining sector. For example, in the Philippines, there are labor abuses of workers in the nickel mining sector, according to a report produced by Amnesty International. In the United States, violations have been reported at the EV manufacturing stage, where workers have been subject to racial and gender discrimination, harassment, and retaliation, for example, at Tesla.

In addition to labor rights, other human rights violations have been well documented in the supply chain. For example, lithium extraction from brines in arid regions of Chile, Argentina, and Bolivia are water-intensive and have been tied to adverse impacts on agricultural activities, reduced vegetation for grazing livestock, and water contamination. Nickel mining in Indonesia, for example, has been responsible for large swaths of deforestation, and waste from nickel tailings has resulted in mass die-offs of fish populations. Even more common, mining projects all around the world have violated the rights of indigenous peoples, especially the right to free, prior, and informed consent.

The five most important transition minerals needed for li-ion batteries and some of the corresponding human rights concerns.

The EV transition has been viewed as a solution for securing a greener future, but human rights and environmental rights must not be violated in the name of sustainability. Currently, the complex and global EV battery supply chains are fraught with human rights violations, with especially egregious violations taking place in the mining sector. As countries look to domesticate their EV supply chains, special attention should be paid to the communities across the globe in which mining and production activities are currently being conducted. Similarly, since EV battery technologies and chemistries have been changing so rapidly, the transition minerals of today may not be the same as those of tomorrow. As such, mining practices should be cognizant of the implications of these changing mineral demands. A sustainable future is only possible if humans, and their rights, are placed at the center of not just the goals themselves, but of the means of achieving such goals.