Shifting Gears Part II: Indigenous Peoples’ Rights and Mining in the U.S.

The transition to green energy technologies, like electric vehicles (EVs), will require a massive amount of transition minerals. EV’s require, on average, six times the mineral inputs of conventional cars. For example, the International Energy Agency predicts, that under the Sustainable Development Scenario (SDS),[1] between 2020 and 2040, demand for lithium will increase by 43 times, nickel by 41 times, cobalt by 21 times, manganese by 17 times, and graphite by 25 times. In order to fulfill the demand for transition minerals, the mining industry has been seen as an important player.

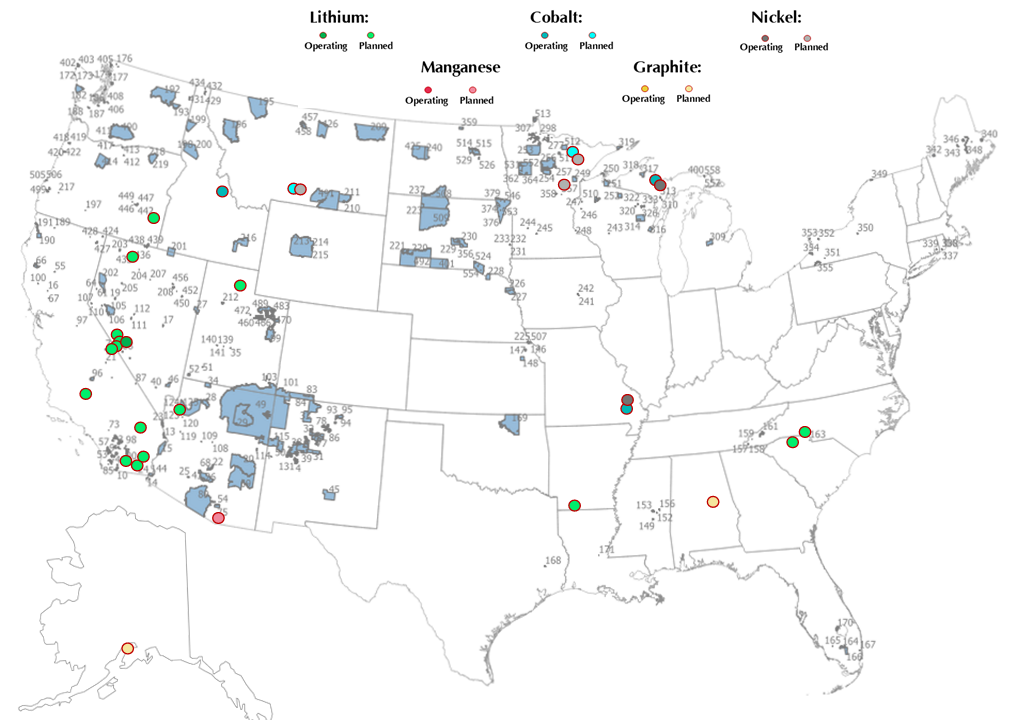

In the United States, the Biden administration has committed to guaranteeing EVs make up 50% of all new car sales by 2030. To meet the rising demand in transition minerals for electric vehicles, the Biden administration has put in place a comprehensive plan to bring EV mineral extraction and processing into the U.S. While clean energy goals are critical, environmental groups have expressed their concerns around the environmental damage that would occur as a result of an increase in mining in the U.S. In addition to the lasting environmental harm, mining activities disproportionately affect Indigenous communities. According to a notable MSCI study, many of the transition mineral deposits in the U.S. are located near or within culturally or environmentally important areas to Indigenous Peoples. In fact, “97% of nickel, 89% of copper, 79% of lithium and 68% of cobalt reserves and resources in the U.S. are located within 35 miles of Native American reservations.”

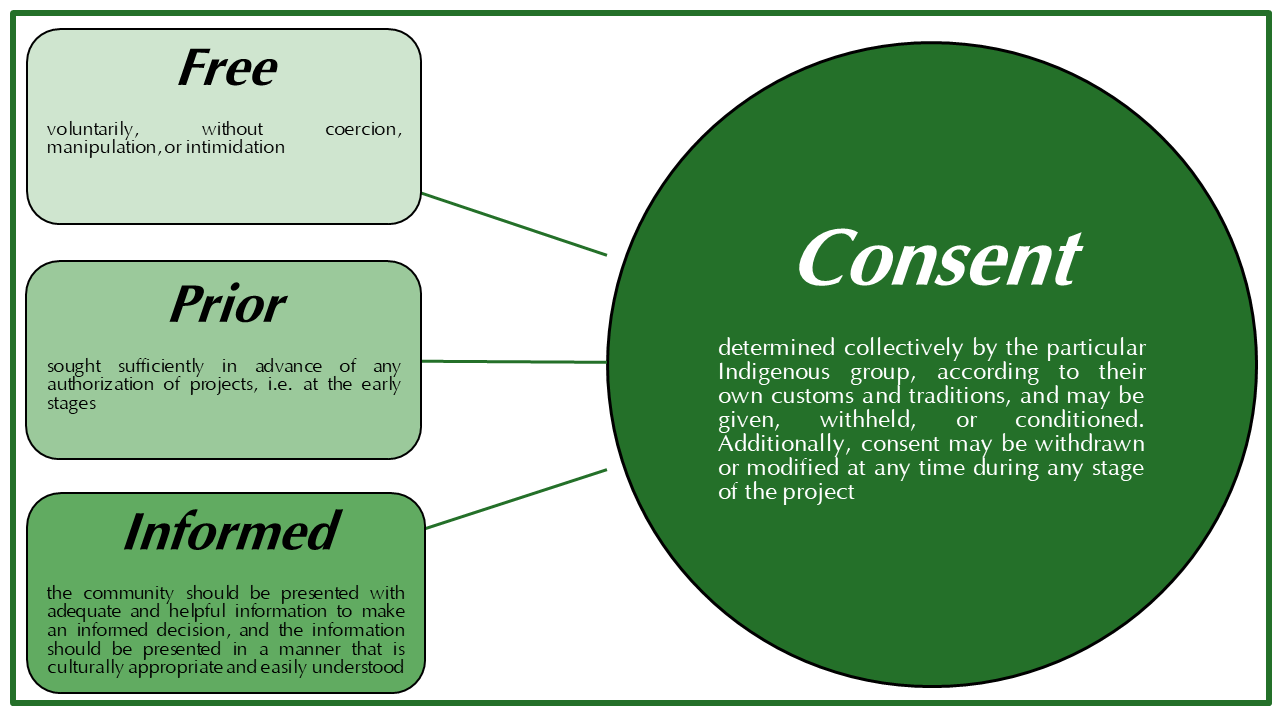

As will be mentioned in this blog, the proximity of mining to Indigenous lands creates a significant risk of violations of Indigenous Peoples’ rights. Mining, including mining waste, continues to cause significant environmental damage, polluting water sources, harming animal and plant life needed for subsistence, and negatively impacting the livelihoods of Indigenous Peoples. Studies have also shown the lasting, negative health impacts, such as chronic illnesses, of mining pollution on Indigenous communities. Further, since many mining operations are located on unceded Indigenous Lands, mining often destroys or negatively impacts places of cultural and spiritual significance for Indigenous Peoples. Additionally, the creation of “man camps” (i.e. temporary housing for mine workers) near mining operations has been linked to increases in violence in Indigenous communities, especially against Indigenous women, girls, and two-spirit people. As will be discussed in this blog, Indigenous Peoples’ right of free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC) is central to respecting participatory rights and land rights. FPIC allows Indigenous Peoples to negotiate with governments and companies as equals, withholding or conditioning consent according to their self-determined priorities.

The transition to clean energy is critical to combatting the climate crisis, but mining for transition minerals must not repeat cycles of violence, suppression, and exploitation of Indigenous communities.

The Right to Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC)

The global authoritative framework on the rights of Indigenous Peoples is found in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). While the UNDRIP itself is not legally binding, it serves as a legal framework for “the minimum standards for the survival, dignity and well-being of the indigenous peoples of the world.” After initially opposing the UNDRIP, the United States formally endorsed it in 2011, citing its commitment to “serving as a model in the international community in promoting and protecting the collective rights of indigenous peoples as well as the human rights of all individuals.”

Central to Indigenous Peoples’ rights is the right of free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC), when it comes to matters that could impact their lands, territories, and cultural and religious practices. The following is a basic understanding of the interconnected FPIC elements:

According to the UNDRIP, before the approval of any project that may affect Indigenous Peoples’ lands, territories, or resources, states must work in good faith with Indigenous communities to obtain FPIC. Through the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs), this also applies to companies. FPIC represents social license to operate, since business activities that violate Indigenous Peoples’ rights often undermine a company’s credibility and result in financial loss for the company. Material risks companies may face for causing or contributing to Indigenous Peoples’ rights violations include reputational damage, project delays and disruptions, litigation, and criminal charges.

The State of Affairs in the United States

The Biden administration’s historic electrification goals, which include increased EV production, onshoring of EV supply chains, and tax incentives, are increasing mining for transition minerals. The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and the Inflation Reduction Act provide for an increase in researching transition minerals mining in the U.S., tax credits for purchasing EVs with a large percentage of U.S.-sourced transition minerals, and tax credits for mining companies extracting transition minerals in the U.S.

According to an ATLAS Public Policy report on the EV transition, there are currently 6 operating transition minerals mines and 24 announced projects underway.

Transition Minerals Mines in the U.S. and Native American Reservations (indicated in blue)

It has been well documented that mining disproportionately affects Indigenous Peoples. For example, a recent study published in Nature Sustainability found that 54% of mining projects globally are located on or near Indigenous Peoples’ lands. In the United States, 79% of lithium, 68% of cobalt, 97% of nickel, and 89% of copper reserves and resources in the U.S. are located within 35 miles of Native American reservations.

In the United States, FPIC has not been incorporated into domestic laws. Despite its endorsement of the UNDRIP, the U.S. does not support the right to FPIC. Instead, projects that may affect Indigenous Peoples are often governed by an unofficial process of consultation, not FPIC. As a result, mining projects may move forward without consent, and even with opposition of impacted Indigenous communities.

Mining in the U.S. is governed by the outdated General Mining Act of 1872, which has remained largely unchanged for more than a century. The Act coincided with westward expansion in the U.S. and supported other policies that displaced Indigenous Peoples. The General Mining Act has no provision for FPIC and is considered one of the least protective mining laws in the world.

FPIC is also largely absent from automakers’ policies. Lead the Charge, a coalition of which IASJ is a member, recently assigned scores to 18 of the largest automakers. General Motors was the only company to have a policy that respects Indigenous Peoples’ rights as defined by the UNDRIP. However, General Motors’ recent investment in a lithium mine undermines its commitment to the UNDRIP. Lead the Charge’s scoring revealed that the respect for Indigenous Peoples’ rights category was the lowest-scoring category, with two-thirds of automakers receiving 0%, and the highest scorer, only 17%. Due in part to automakers’ lack of commitment to Indigenous Peoples’ rights, mining projects have already (or will) violate Indigenous Peoples’ right to FPIC.

The following section highlights just a handful of the many instances in which mining companies are violating Indigenous Peoples’ rights in the U.S.

Thacker Pass (Nevada)

Thacker Pass in Humboldt County, Nevada has been the site of extensive Indigenous Rights violations by a Canadian mining company, Lithium Americas, for the past few years. The area, which comprises about 5,000 acres, forms part of the traditional and unceded territory of the Paiute and Shoshone peoples, and is categorized as U.S. public land. In addition to the devastating ecological and environmental impacts associated with lithium strip mining, the mine would also destroy an area held sacred by the Paiute peoples. In 1865, Thacker Pass was the site in which members of the Nevada cavalry massacred 30-50 Paiute peoples. In fact, the People of Red Mountain, made up of Paiute and Shoshone peoples, stated “[t]o build a lithium mine over this massacre site in Peehee mu’huh [Thacker Pass] would be like building a lithium mine over Pearl Harbor or Arlington National Cemetery. We would never desecrate these places and we ask that our sacred sites be afforded the same respect.”

Despite absence of consent from the many Indigenous Peoples in the area, the lithium mine was approved in January 2021. Notably, the mining permit approval process was fast-tracked, which meant the process went faster than the normal mining permit process in the U.S.

In February 2021, four environmental groups filed a lawsuit against the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) alleging the BLM violated federal statutes in granting the permit for the mine. Months later, two Indigenous groups joined the lawsuit against the BLM. In February 2023, the judge ruled that although the BLM violated one of the statutes in question, construction of the lithium mine could proceed.

Subsequently, the parties to the lawsuit appealed the decision, and three Indigenous groups filed another lawsuit against the BLM. The legal battle over Thacker Pass continues, but Lithium Americas has already started construction on the mine. Despite the ongoing legal proceedings and the lack of social license to operate, General Motors announced in January 2023 its plan to invest $650 million in the Thacker Pass mine.

Oak Flat (Arizona)

In Arizona, Indigenous Peoples have been fighting to protect a sacred site from a copper mining operation. Known as Oak Flat, the site of the 2,400-acre proposed copper mine is located on the Apache peoples’ sacred land, an area they call Chi’chil Biłdagoteel. According to Apache leader, Wendsler Nosie Sr., constructing the mine would interfere with his people’s constitutional right to practice their religion, remarking “[w]ould anyone destroy Mount Sinai to drill for oil?”

The San Carlos Apache Tribe has been actively opposing the copper mine project, since land was approved to be given to the international conglomerate mining company in 2014. Although these efforts have stalled the construction of the mine, the U.S. Forest Service is still undertaking its environmental impact statement, despite the Biden administration’s promise to extensively consult with local Indigenous Peoples before finalizing the land swap.

In 2021, the Apache Stronghold—a coalition of Apaches, other Native peoples, and non-Native allies dedicated to preserving Oak Flat- sued the U.S. government for violating the Religious Freedom Restoration Act and an 1852 treaty between the U.S. and the Apache peoples.

The lawsuit asks for the government to halt the transfer of land to the mining company. Although the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals decided not to protect Oak Flat from being transferred in June 2022, it later determined that it would rehear the case. Notably, a coalition of religious groups (The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Seventh-day Adventists, the Islam and Religious Freedom Action Team of the Religious Freedom Institute and the Christian Legal Society) banded together to file an amicus brief in the case. On March 21, 2023, an eleven-judge panel of the Ninth Circuit heard oral arguments and is now in the process of making a final decision. There are currently two additional lawsuits against the U.S. government for violating environmental and historical preservation statutes.

Salton Sea (California)

In Imperial County, California, the fight to protect the Salton Sea from a proposed lithium extraction site is just getting started. Experts believe the Salton Sea could potentially hold the largest lithium deposit in the U.S., which could be extracted from lithium brine. The Salton Sea, a large saline lake with about 130 miles of shoreline, forms part of the Colorado River Delta. Over the span of thousands of years, the lake has repeatedly dried up and refilled again. For the past decades, the Salton Sea has acted as a collection basis for agricultural runoff from local operations. The accumulation of fertilizers and pesticides in the lake have caused mass fish die-offs, and have created toxic vapors that make the air quality poor.

The site of the proposed lithium extraction sits on the ancestral lands of several Indigenous communities, who have not given their consent. Quechan and Kamyan leader, Preston J. Arrow-weed, opposes the lithium extraction project, stating “My biggest fear is that mining in the California desert could contaminate the aquifer we depend on for our drinking water, and even reach the Colorado River.” Additionally, the Quechan tribe has formally objected to the lithium project in a letter sent to the Lithium Valley Commission, which is part of the California Energy Commission. According to the letter, the Quechan peoples were not consulted with, even after requesting consultation. Additionally, the proposed project would disturb a sacred site for both the Quechan and Kamyan peoples, Obsidian Butte. At a July 2022 public meeting, other Native American tribes expressed deep concerns over the consultation and impacts review processes.

Challenges and Opportunities

Mining for EV minerals and renewable energy resources in the U.S. is exponentially increasing, and with it, violations of Indigenous Peoples’ rights. While an increase in mining activities is likely, in order to meet transition mineral demand, alternatives, such as battery recycling and repurposing abandoned mines, should be prioritized. When mining projects are considered, Indigenous Peoples’ FPIC definitions and protocols must be comprehensively addressed to ensure Indigenous Peoples’ rights are not violated and to prevent harm from coming to Indigenous communities. Similarly, FPIC should be operationalized in ongoing mining operations. Mining projects that violate FPIC may delay or even halt operations, resulting in financial loss.

Since many mines are not yet in operation, there is still opportunity to operationalize FPIC in the EV transition. While there is some movement towards reform in the mining industry, automakers can play a vital role in their supply chain investments and sourcing. Withholding investments in or refusing to source from mines that have violated Indigenous Peoples’ rights can be a powerful tool for automakers, given their influential position.

[1] The Sustainable Development Scenario (SDS) represents a future reality based on the necessary measures to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement.