An Illusion of Social Justice: The Problem with Corporate Philanthropy

May 13, 2024

In the wake of George Floyd’s murder in 2020, US companies pledged a whopping $200 billion to advance racial equity. In spite of scandals and poor track records, major corporations committed to be a force for social change and to fight racism. Four years later, we’re left to wonder where all that money went. A Washington Post investigation found that the vast majority of corporate pledges were allocated as loans or investments that companies stand to profit from, with only a small fraction going to groups actually connected to Black Lives Matter. We’ve yet to see the transformative racial equity changes that we were promised in corporate solidarity tweets and multi-billion dollar pledges. The racial wealth gap continues to grow, and hate crimes are on the rise. Nevertheless, corporate philanthropy continues to be touted as a solution to negative social impacts. Companies are spending billions to “do good” for our communities and environment. But is that what corporate philanthropy is really about?

What is Corporate Philanthropy & How Does it Work?

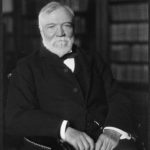

Corporate philanthropy in the US has its origins in the post-industrial revolution era. Wealthy individuals like Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller shared their fortunes by establishing charities and donating to public institutions. Though these fathers of philanthropy have an enduring reputation as generous do-gooders, many have pointed out the fallacy in their legacies. Both Carnegie and Rockefeller’s businesses were connected to poor labor conditions, low wages, and violent oppression of worker rights. They donated millions to support public welfare, all the while making billions off exploitative practices. Despite donations to libraries and hospitals, both men earned reputations as “robber barons” for their ruthless business practices.

Corporate philanthropy in the US has its origins in the post-industrial revolution era. Wealthy individuals like Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller shared their fortunes by establishing charities and donating to public institutions. Though these fathers of philanthropy have an enduring reputation as generous do-gooders, many have pointed out the fallacy in their legacies. Both Carnegie and Rockefeller’s businesses were connected to poor labor conditions, low wages, and violent oppression of worker rights. They donated millions to support public welfare, all the while making billions off exploitative practices. Despite donations to libraries and hospitals, both men earned reputations as “robber barons” for their ruthless business practices.

Today, we see this dynamic reflected in the corporate philanthropy landscape. The term “reputation-washing” has been used to describe a tactic of companies spending a small amount of money, very publicly, to address a problem that the company itself has created and actively profits from. For example, major oil and gas companies like BP and Exxon tout philanthropy initiatives to provide humanitarian relief after natural disasters. All the while, their fossil fuel operations worsen climate change and exacerbate natural disasters in the first place. BP’s “hundreds of millions of dollars” in donations to relief charities over the past 70 years pales in comparison to its billions in annual net income as one of the highest greenhouse gas-emitting companies in the world.

Today, we see this dynamic reflected in the corporate philanthropy landscape. The term “reputation-washing” has been used to describe a tactic of companies spending a small amount of money, very publicly, to address a problem that the company itself has created and actively profits from. For example, major oil and gas companies like BP and Exxon tout philanthropy initiatives to provide humanitarian relief after natural disasters. All the while, their fossil fuel operations worsen climate change and exacerbate natural disasters in the first place. BP’s “hundreds of millions of dollars” in donations to relief charities over the past 70 years pales in comparison to its billions in annual net income as one of the highest greenhouse gas-emitting companies in the world.

How Corporate Philanthropy Causes Harm

Beyond covering up bad practices, corporate philanthropy can be used to bolster corporate profits and increase social inequality. Philanthropy can divert resources from the public sector by allowing companies to avoid paying their fair share in taxes. Some of the wealthiest corporations in America pay next to nothing– or actually nothing- in federal income taxes each year. Chevron is one of the most profitable companies in the world, yet it paid no federal income taxes in 2018 and paid only $174 million in federal income taxes in 2022, an effective tax rate of 1.8%. Chevron proudly highlights its charitable work in Kazakhstan to improve public infrastructure and protect endangered birds. However, Chevron’s operations in Kazakhstan are connected to decades of environmental disasters, tax evasion, and criminal allegations. Chevron generates billions of dollars in profits from its Kazakh operations, where it serves as one of the largest polluters in the country. Yet, it cites its philanthropy as proof that Chevron has done good in the region.

As a whole, US corporate giving represented $21 billion of all funds towards social progress in 2022. There is a myth that the private sector can carry out social services faster and more efficiently than the public sector, but studies have increasingly found that this is untrue. Through philanthropy, corporations have disproportionate influence over how “social progress” resources are allocated. Needless to say, that is a concerning notion. Companies are unlikely to fund groups that push for stronger regulation or seek to hold corporations accountable. Instead, they can use philanthropy to divert attention away from their impact while still maintaining a good public image.

Another Arm of Corporate Power

At its worst, corporate philanthropy is a tool to solidify company influence and reinforce their political power. Some companies use donations to pay off or co-opt communities in order to silence dissent. A 2024 investigation spotlighted power companies who courted and paid off Black civil rights leaders to block renewable energy projects like rooftop solar. Black and Brown communities are disparately affected by climate change, and thus stand to benefit the most from renewable energy. Duke Energy, one of the companies implicated in the investigation, is a major emitter of greenhouse gasses and a source of toxic pollution in the US. Its charitable foundation lauds investments in climate resilience and community development. All the while, its operations exacerbate the climate crisis and the company aggressively lobbies against US climate policy.

Corporate philanthropy is not accountability. It’s not even a good corporate sustainability approach. When exploited, companies can use philanthropy to control the public narrative, suppress calls for regulation, and silence opposition. Even at its best, corporate giving allows companies to acquire funds via exploitative practices and use the excess to shape the landscape of “social good” in our communities. We deserve more than this illusion of justice. Companies should be paying their fair share in taxes and mitigating their negative impacts. When “doing good” is just another arm of corporate power, we need to invest in tactics that actually promote social justice.

Jillianne Lyon, Program Director